When data flows over a TCPIP connection there are several factors which control the rate at which data can be sent. You can influence some of these factors.

Data is sent as packets typically of size about 1440 bytes – because old hardware could only support this. You could use larger packets, but you may hit a router which chops it into smaller blocks.

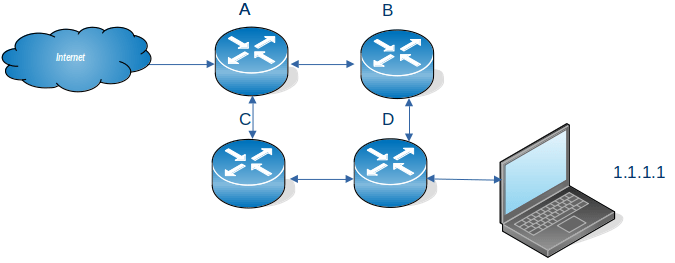

The basic TCPIP flow

Consider a Client Server connection. The client application wants to send some data to a server application

- The client uses send() to put some data into a TCPIP buffer and returns.

- TCPIP sends some data (a packet) from this buffer, sets a timer and waits.

- The server receives the data, end sends back an ACK saying so far I have received this many bytes from you.

- The application on the server does a receive (if there is no data, the application is suspended until data arrives). If there is enough data to satisfy the receive, the application returns, otherwise it is suspended.

- At the client end, when TCPIP has received the ACK. It no longer needs the data which has just been acknowledged. It can send more data.

- If no ACK was received and the timer has timed out, TCPIP resend the data.

There are several parts to this:

- Putting things into the pipe – the send buffer

- The pipe

- Getting things from the pipe, the receive buffer

The send buffer

- TCPIP has a buffer for its use.

- The application

- An application does a send() and passes data to TCPIP.

- If there is space in the TCPIP buffer, the data is moved into the buffer, and the application returns.

- If there is not enough space for all of the data, enough data is moved to fill the buffer, and the application waits until more space is available in the buffer.

- When all of the data has been passed to the TCPIP buffer, the application returns, and can do more application work.

- TCPIP

- TCPIP takes a chunk of the buffer (a packet) , sends it over the network, and sets a timer.

- It can then process another chunk of data, and send it over the network, so there are multiple packets in flight.

- When the far end has passed the data to the application, it sends the ACK back.

- The local end, when it has received the ACK for a chunk of data, knows the data has been received by TCPIP at the remote end, it no longer needs to keep a copy of the data, and frees up the space on the buffer.

How big a buffer is needed to get good throughput?

The data is held in the TCPIP buffers; waiting to be sent plus the round trip time; from when the data was put into the TCPIP buffer, to getting the ACK back. This could be 10s of milliseconds. Multiple packets can be in-flight (perhaps 10s or 100s) which improves the throughput. So send 10 packets; wait, when the first ACK is received, send another packet etc., so there are always 10 packets in flight.

If the buffer is too small the application has to wait. Increasing the send buffer size will increase throughput up to a point (when the application does not have to wait) after this point making it larger may make no difference.

As more data is in flight, the connection needs a bigger send buffer.

An application can set the send buffer size using the SETSOCKOPT call. If this is not used, then there will be a TCPIP default send buffer size. On z/OS this is the system wide TCPCONFIG TCPSENDBFRSIZE …. parameter.

The default used to default to 16KB, and currently is typically 64KB. There is a TCPIP enhancement which says if the send buffer size is larger than 64KB, then TCPIP can dynamically increase it if it will improve performance. See Outbound Right Sizing(ORS).

Note: If you change the system wide send buffer size (TCPCONFIG TCPSENDBFRSIZE on z/OS), this will affect all applications that do not set the size using SETSOCKOPT. You should test this before putting it into production because it may affect many applications.

The receive buffer

At the receiving end, TCPIP has a buffer. Data from the network is put into this buffer. After the data has been put into the buffer, TCPIP sends back an ACK with three fields saying

- so far I’ve received this many bytes from you

- I’ve sent you this many bytes

- my buffer has space for this many bytes

An application does a receive to get the data, if there is insufficient data to satisfy the receive, the application can wait, or return just the data in the buffers, depending on the options.

If the receive buffer is full, any incoming data will be thrown away. If the application does receive the data, then does lots of processing on the data, followed by receive more data etc, the receive buffer may fill up. Some applications receive the data, give the data to a subtask to process, immediately do another receive, and so try to keep the receive buffer empty.

If the amount of arriving data is larger than the free space in the buffer, TCPIP will return “no space left in the buffer” as part of an ACK. The sender then knows to wait. When the application receives the data, and makes space, “x bytes are available in the buffer” is sent as part of the ACK, and the sender can start sending data again. This “space available” is known as the Window Size, and helps regulate the flow of data.

If you think about this for several minutes, you will realise that there is a time lag between the receive available buffer size going to zero, and the sender receiving the ACK saying no space in receive buffer. Any in-flight packets may get thrown away, or the end application may get all the data from the buffer. The “no space left in receive buffer” tells the sender to stop sending data until there is space in the buffer, and the sender may then reduce the amount of in-flight data.

Having a zero sized window means there is a problem that the application is not getting the data from the buffer fast enough.

How big a receive buffer is needed to get good throughput?

If the buffer is too small the application has to wait, and packets may be thrown away.

An application can set the receive buffer size using the SETSOCKOPT call. If this is not used, then there will be a TCPIP default receive buffer size. On z/OS this is the TCPCONFIG TCPRCVBFRSIZE …. parameter.

The maximum receive buffer size is specified in TCPMAXRCVBUFRSIZE.

If the receive buffer size is greater than 64B, then a performance enhancement called Dynamic Right Sizing(DRS) can come into action which automatically increases the buffer size up to 2MB.

Inside the pipe

I have described the sender side filling the send buffer for the connection, and the application on the receiver side taking data from the connection’s receive buffer. I’ll look at the pipe in between.

Data is send across the network in packets. The packets are usually small – for example 1500 bytes for Ethernet. Some protocols support larger packet sizes. Data send within a z/OS can have 56KB packet sizes. The Maximum Segment Size (mss) is the maximum size of the user data in a packet.

If a packet is too large for a device, it may be cut into smaller chunks and then passed on – or the packet may just be dropped.

The simplest and slowest transmission is send one packet and wait for the ACK, then send another packet.

It is much more efficient to send multiple packets. For example send 10 packets, when the first ACK comes back (saying the first packet has been received), send the next packet and so on, so there are always 10 packets (or less) in the pipe.

The amount of data on the network is limited by the smaller of the send buffer size and the receive window size. This means you need both a big send buffer, and a big receive buffer to get maximum throughput.

The TCP window is the maximum number of bytes that can be sent before the ACK must be received. If the network is unreliable it is better to keep the window small to reduce the amount of data that needs to be resent after a missing ACK.

Where can I get more information?

I wrote a blog post about tuning MQ channels which gives additional information.

How do I display this buffer information?

On z/OS you can use

- TSO NETSTAT CONFIG command reports the default receive buffer size, the default send buffer size, and the default maximum receive buffer size

- TSO NETSTAT ALL (IPPORT nnnn where nnnn is the port number.

- TCPMON on GITHUB to monitor the buffer and window sizes in near real time.

On Linux

You can use the command

- ss -im -at ‘( dport = :21 )’ which displays information about connections with destination port of 21.

- ss -im -at ‘( dst = 10.1.1.2 )’ which displays information about connections with destination ip address of 10.1.1.2

Is there more information available about buffers and windows?

There is a lot of information on the web, but it is not usually easy to digest.

I thought this article was clear about the different buffers and windows.

How do I change the buffer sizes?

An application can change them using the SETSOCKOPT call see here options SO_RCVBUF and SO_SNDBUF

With some applications, they have a specific way of setting the buffer sizes

- MQ for midrange RcvBuffSize etc

- MQ on z/OS use +cpf RECOVER QMGR(TUNE CHINTCPRBDYNSZ nnnnn)

+cpf RECOVER QMGR(TUNE CHINTCPSBDYNSZ nnnnn)

- FTP on Linux -x option

Otherwise the system defaults are used.

Other information provided with display commands

Commands like netstat provide other information

For example

- round trip time – this is average time in millisecond taken for a packet to be sent over the network, and the ACK is received

- RoundTripVariance – this gives the spread of the response times. It is the sum of the square of each response time. A measure of the spread of the response times is the standard deviation = sqrt((the variance – average round trip time ** 2) /N) where N is the number (of packets sent). If all the packets have the same round trip time, this will be close to zero.

- Local 0 window count – the number of times there was 0 space in the receive buffer

- Remote – window count – the number of times the remote end had 0 space in its receive buffer.